Princess Mononoke - Must Be Written

Needless to say, Miyazaki Hayao's animations are modern classics. Studio Ghibli has become the new Ukiyo-e and created an enormous cultural sensation in the 21st-century film industry. However, unlike his attention to artistic designs and technique, Miyazaki's sophisticated philosophical narratives haven't been acknowledged in public discourse. Nonsensical claims, such as saying that Miyazaki is inclined to the right wing, are indicative of the general lack of serious consideration and understanding of Miyazaki's philosophy. Although recently, directors like Shinkai Makoto are enjoying instant fame for their technical prowess and are even being called 'post-Hayao', the integrity of his historical and aesthetic perspectives, and the depth of discourse in his films, prove that Miyazaki is without equal.

Miyazaki's animations have three distinctive themes: The ecological discourse of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke; the anti-fascism of Porco Rosso and Howl's Moving Castle; and the commodity fetishism of Spirited Away. All of Miyazaki's films share these three discourses and thematically support each other, reinforcing the aesthetic construction of each film. In this way, Princess Mononoke, the best of Miyazaki's animations that speak on nature, also contains some of Howl's anti-fascism and Chihiro's mythical power. However, the simple categorization of it as a so-called 'nature animation' reduces the unprecedentedly unique discourse of Princess Mononoke to nothing more than an eco-friendly message. Although Princess Mononoke's plot and artistic background might seem similar to that of Nausicaä, the film bravely repudiates the reinforcement of a naive binary opposition and successfully unites eco-feminism with the dialectic of enlightenment.

The film begins as Ashitaka leaves his town in search of a cure for the curse he got from killing a nameless god who'd become a demon. Before he's very far from his hometown, Ashitaka encounters war and the smell of slaughter. Unlike Miyazaki's other films, Princess Mononoke is not reluctant to display brutal images in pastel tones. The aspect of the war is gory: High-class samurai slaughter the farmers, and the monk Jigo says the era they live in is a 'disastrous time.' Humans struggle to survive this disaster, yet the weak have neither power nor means to subvert the existing power structure. One should remember that even Ashitaka is from a town populated by those who were defeated at war, and has become nothing more than a wanderer who can't return to his declining home. The Muromachi period in Princess Mononoke is a time when the weak can't be free from the fear of a resentful death; an era when life itself, merely being alive, is disastrous.

However, as Ashitaka reaches Tataraba, the town established by Lady Eboshi, the gloomy atmosphere of the film is overturned. Most criticisms of Princess Mononoke show a lack of thorough observation of Eboshi and treat her as just another bad guy or a villain representing human selfishness. However, this careless approach ignores the fact that Eboshi's Tataraba is a place where women, lepers, farmers, and people from all the weakest classes live free from the atrocities of the samurai. Even Ashitaka is fond of this town, saying 'Happy women make a happy village,' and lepers, who were historically subject to abjection, find their purpose and realize themselves there. The peace of Tataraba comes from iron and mining; the power of iron allows them to fight against the traditional knight class, the samurai. Eboshi and the people of Tataraba are filled with deep-seated rancor against the forest gods who sabotage their mining and transportation and willingly wield the power of iron to destroy nature. This ironic confrontation between the two worlds leads the film's discourse to Adorno.

Theodor Adorno

‘Can poetry be written after Auschwitz?’

Theodor Adorno agreed that the power of enlightenment brought human life to a different level. In Hobbes' natural state, humans live as animals, struggling, surviving, and killing each other. Amidst this horror, humanity dreamed of controlling power that seemed uncontrollable, of overcoming the wave of disasters, and of the liberation of human existence. The so-called 'will to live,' or 'conatus' (Spinoza), was the oldest desire humans ever had, and in pursuit of this, humanity has freed itself from the destructive power of nature. Using human reason and enlightenment as a sword and shield, the fear of nature slowly disappeared, and the law of civilization replaced the law of the jungle. Tataraba embodies the power of enlightenment. As long as they have guns and the fire of civilization, no samurai can reach the women of the town. On top of this, unlike Ashitaka's hometown, which was almost destroyed by a single nameless god, and unlike other small villages which are destroyed by floods and war, Tataraba is an impregnable fortress against which not even the old gods of nature can stand. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that the film began with the appearance of a nameless god that had become a demon. Adorno was never positive or affirmative about enlightenment itself.

Although humanity was freed from their fear of nature, they bound themselves to a system designed by human reason. To stand against nature's massive power, all members of society must work accurately and efficiently according to the given rules. Universality was invented, and individual diversity and different characteristics were suppressed for the safety and efficiency of the group. Everything was transformed into objects that were only valuable for their use for the convenience of a better-functioning massive machine-like system, including humans. Humans became mechanical parts of this very machine called enlightenment.

To build this massive civilization amongst the horrors of nature, one should change the foundation of every action—the perspective. Nature reflected in the eye of enlightenment is no longer mysterious and somewhat beautiful but a compilation of parts that can be assembled and disassembled for certain purposes. This rationalistic perspective arms man materialistically and spiritually to command nature (Bacon). On the other hand, what is considered useless by human reason, which in the end is a product of the epistemological frame of the era, becomes treated as an abject and discarded accordingly. Nature becomes a collection of disposable parts in the light of human reason, and humans are to be controlled and suppressed for the quality of civilization, and civilization accelerates the objectification of both nature and humans. The never-ending tragic cycle, the Dialectic of Enlightenment, has finally engulfed the world.

"When the forest has been cleared, this desolate place will be the richest land in the world."

Nature in Princess Mononoke is thoroughly destroyed and humiliated by the power of enlightenment. The old gods from the forest kneel helplessly before Eboshi and the people of Tataraba, and even the Forest Spirit itself is killed by Eboshi. Therefore, Eboshi is not simply a villain but is a multi-dimensional character who portrays the complications of human existence. She takes care of lepers and welcomes friendless farmers and women, but at the same time, doesn't hesitate to objectify the forest for the betterment of her town. To her, the cow herders who fell off the cliff are a replaceable labor force, and the Forest Spirit is nothing but a promised reward from a king.

It must be remembered that Ashitaka, the wanderer, can’t settle in Tataraba and must leave again. It seems enlightenment freed people from the violence of nature, but as one can see from Adorno's study, it trapped humanity in another violent cycle. Even though Eboshi's weapons save the weak, wars are still fought, houses are still burned, and blood is still shed. The structure that results in the slaughter of the weak hasn't been altered at all. Rationalism, built on enlightenment, defines the boundary of what is 'reasonable' and destroys everything that is outside the perimeter, as European powers did in America and Africa. Consequently, Ashitaka, who left the village built by the defeated people, has no choice but to return to the road. Tataraba, too, will be a town of the dead when others invent new, more powerful weapons.

Through an endless showcase of brutal images, the film reaches the climax of its Dialectic of Enlightenment in the mountains of dead boars. Miyazaki said that the Muromachi period, like modern Japan, was a time of accelerated dangerous progress. Miyazaki himself is a relevant part of one of the worst results of the Dialectic of Enlightenment: The Japanese empire. From Porco Rosso to Howl's Moving Castle, the old man who remembers what a reasonable human can do to another has never gone easy in his criticisms of that bloody history. In Princess Mononoke, the film goes further than just having a metaphorical aesthetic structure and displays straightforward images of carnage and genocidal bloodbaths.

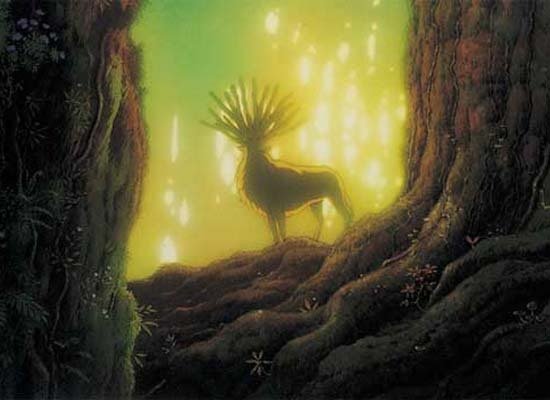

'With us or against us.' Dividing the world into radical dichotomous categories and frantically sharpening the instrumental reason only made humans 'war-machines' (Deleuze) that focused solely on self-preservation. Ironically, the enlightenment that humanity once believed was a savior from disaster culminated in the unprecedented reasonable carnage called world wars. Although Miyazaki's animations do not hesitate to reveal the devastation of the world, they have always shown attempts to heal the wound. Princess Mononoke explores the source of madness in history and discusses an alternative route for a better future at the same time. To understand what Ashitaka realized between humans and nature, one should seriously consider that the film has Shinto as its main aesthetic concept. The belief that everything in the world has a soul is a typical pantheistic perspective. This point of view brings the spotlight back onto what the modern perspective on nature twisted and redacted on purpose.

As the Forest Spirit is one with Night-Walker, the God of Death,

there was no binary opposition in nature before human reason invented it.

The rationalist dominion over nature separates subjecthood from nature and amends otherness, or if that's impossible, eliminates it. However, what is considered abnormal is not how it was from the beginning. Life and death, man and woman, light and darkness, natural and chemical; binary opposition is an imaginary system on which universality and rational signifier-signified relationships heavily depend. (Derrida. J) In alliance with logocentrism, enlightenment separates death from life and preaches to people that only life is objectively and omnipotently righteous.

However, the above-mentioned pantheistic perspectives operated in a different way. Indigenous Americans thought their deceased ancestors came to visit them in the shape of animals. The traditional belief in Korea also says that life comes from the soil and returns to the soil. A change in perspective leads to a change in action. Repudiating such a violent separation puts a brake on the control over nature which results in control over otherness.

The film displays such aspects with mise en scenes and metaphorical lines. Moro says the Forest Spirit gives life but also gives death. The wise wolf doesn't reject death as abnormal. In nature, death is one with life and is a transformation, not the end of existence. The scene where the Forest Spirit saves Ashitaka implies commingled death and life in nature. The Forest Spirit's steps cause the flowers to blossom and simultaneously wither them. Moro's severed head moves by the Night-Walker’s death and punishes the retaliator. At the end of the story, new life sprouts where the god of death dies. The binary-opposite antithesis that humanity tried so hard to degrade turned out to be one with the thesis. Therefore, where binary opposition shatters into pieces, humans and civilization become part of nature. As Adorno says, all humans have nature in themselves, and dominion over nature leads to dominion over ourselves, as we are 'being-in-the-nature.'

"We might find a way to live together."

Nevertheless, no one can completely refuse to admit the power of enlightenment. Adorno himself didn't disregard the evident difference between nature and civilization. The power of enlightenment indeed liberated human existence to a degree and allowed the self-realization of human existence in history. What matters is a reconciliation that is not a simple, single-dimensional signifier of environmental protection or an eco-friendly attitude. It encompasses all aspects of what the logocentric perspective has torn apart.

Enlightenment exiles otherness that is beyond the perimeter of its understanding, forcing 'universality' on humans and, if it fails, getting rid of them. This kind of violence would intensify the instrumental reason and give birth to the end of civilization. Meanwhile, what some ecologists insist on, such as returning to nature, is suicidal. The ecological anti-vaccine movement, the anti-chemical-product movement, and radical ecologism all disregard the fact that humans cannot exist as human beings in nature without the power of enlightenment.

Repudiating all of those, San, our Princess Mononoke, represents mimetic reconciliation, Adorno's antidote to the dialectic of enlightenment. Mimesis is neither abusive nor self-destructive. Mimesis means 'copy'; for the best example, consider the ancient shamans, who would drape themselves with an animal's fur and copy its movement, habits, and other qualities. Mimesis is another of humanity's methods for evading the fear of nature, but its mechanism lies in assimilation with, rather than dominion over, otherness. By becoming one with nature, a mimetic methodology connects individuals to nature and, by this integration, creates a foundation for coexistence.

As a shaman puts on the skin and behavior of a wolf, calling herself one of them, San runs through the forest in the way of the wolf. She is neither human nor wolf but an anthropomorphized mimetic bridge, like the shamans, who were treated as meta-human. Adorno once called it sinking: A way to reconsolidate by becoming one another. Understanding others leads to coexistence and prevents dominion and control over one another.

The way San and Ashitaka's story develops places the film in the ranks of masterpieces. Ashitaka does not go into the forest with San, and San decides not to live with Ashitaka in Tataraba. One cannot choose only nature or only civilization. Miyazaki is truly aware that the noble and nice-sounding cause of the radical naturalist is nothing but delusion. Instead, the boy and the girl promise to understand and interact with each other.

' We are going to start all over again. This time, we’ll build a better town.'

Princess Mononoke shows much more impressive philosophical advances than Miyazaki's other animations. San can't really be considered an ecofeminist. Although she is powerful and stands against patriarchal dominion, she is more a part of nature and doesn't set foot in civilization. Although Eboshi constructed the town and helped the historically marginalized, until the film's end, Eboshi was closer to a traditional white women-centric kind of feminism, saving only the weak within her own boundary of understanding. She was nothing but another form of patriarchal power.

However, after all is done, in Tataraba, Eboshi gets a second chance. She realizes what was wrong and decides to build a new future, saying, 'Let's start from the beginning again.' Ecofeminism is born when the two characters who had been eager to kill each other finally understand each other. As the Frankfurt School revealed that the binary opposition of enlightenment—creating universality and objectifying otherness—was a delusion, ecofeminism goes beyond women. This philosophy reveals that the abjects of history are nothing more than those who were exiled by the existing power. Understanding this saves not just women but all those abjected specters, from people of color to Holocaust victims. On the strength of this new alliance, Eboshi will build a better Tataraba, where all of the marginalized are saved, a civilization that is free from the dialectic of enlightenment. This is why Eboshi is more than just a villain, and the relationship between San and Eboshi is as important as the relationship between San and Ashitaka.

For the reasons this paper has delineated so far, decorating Princess Mononoke with empty yet plausible words like 'returning to nature or a call for environmental protection.’ is not only superficial but also irresponsible.

Life sprouts where death lies, and people decide to live on together. The Kodama, a symbol of fertility, shows itself in the heart of the ruins, and the love of a boy and a girl promises a new coexistence. Adorno once said, 'There can be no poetry after Auschwitz.' Despite the common misunderstanding, this is actually Adorno asking: 'Can poetry be written after Auschwitz?' A humble yet honest reflection on the birth of the massacre due to a human-centric perspective and a restoration of the once-forgotten who were removed from history, Princess Mononoke is Miyazaki's answer to Adorno's question.